Was the 2020 Election in Indiana Fair? We Don’t Know

by Margaret Menge • Republished with permission of the author. Originally published in Indiana Policy Review Fall 2021 issue.

A lady in a yellow blouse was in the thrall of explaining something to a few others who were leaned into her and hanging on every word, while a man in a red shirt seated behind a long table was showing something on a piece of paper to a couple of others who’d circled around him.

They were so engrossed that they didn’t see me approach and I had to interrupt to get them to notice me.

“Excuse me. Is this where the Indiana Election Commission is meeting?” I asked.

They all stared at me for a couple of seconds.

“It’s over,” one of them said.

“They didn’t take any questions or anything. They just left the building,” another one said.

It was 1:30 p.m. The meeting had started at 1 p.m. How could it be over?

But it was. And those who’d remained in the room . . . I didn’t know them. But I instinctively knew who they were and what they were doing there. They had come to get answers, and they’d stayed because they still didn’t have any, and didn’t know how to get them.

An extraordinary thing happened after the November 2020 election. About every reporter and editor working for every newspaper in America, and every broadcast journalist working for every television station, told readers and viewers that there had absolutely not been any fraud in the election and more or less refused to cover any evidence that pointed to any. They helped provide cover for what will probably go down in the history as the biggest political story of our lifetimes – the theft of a U.S. presidential election on a national scale.

I watched most of the election hearings held in the states.

In a phone conversation earlier this year, Indiana State Sen. Greg Walker, a Republican representing parts of Johnson and Bartholomew counties who sits on the elections committee, told me those hearings were not real hearings, only publicity stunts.

It was stunning to hear a Republican office-holder say something so obviously false.

Most were indeed real legislative hearings.

The hearing in Wisconsin was held in the State Capitol building in Madison on Dec. 11, 2020. It was a joint hearing before the State Senate and the State Assembly election committees and included seven hours of testimony, including from a man who testified that his elderly father’s vote was stolen from him in a nursing home by nursing home employees (he had advanced-stage Alzheimer’s and had no idea a presidential election was even taking place, yet somehow he’d cast a vote). The man had driven 80 miles to beg legislators to do something, pointing out there were more than 300 nursing homes in the state and that if only 10 votes were stolen in each one, you’d have 3,000 fraudulent votes.

This is just the small potatoes.

There were hundreds of thousands of illegal ballots that were counted in Wisconsin, including 170,140 absentee ballots that were accepted without an application when state law says an absentee ballot “shall not” be issued without an application first being received by the clerk, and if it is, it “may not” be counted.

“Shall not.” “May not.” This is very clear language. This is the law, passed by the elected representatives of the people.

But Democrat clerks determined to defeat Trump violated it and suffered no consequences.

At the first state election hearing, held in Pennsylvania the day before Thanksgiving, Rudy Giuliani said in his opening statement that what happened appeared to be a “common plan” carried out in Democrat-run cities in several states to “skew” the election for Joe Biden.

Those states, of course, were Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia, Nevada and Arizona.

It appeared to be a “common plan,” he said, because many of the same things happened in these states, including Republican observers locked out of rooms where hundreds of thousands of ballots were being counted in violation of laws that say that representatives of campaigns and parties, and also members of the media, may observe the count.

It seemed to be just this group of states, with the focus on the big Democratic cities in these states: Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Milwaukee, Madison, Atlanta, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson.

But now another theory has emerged — a theory that not only did the Democratic Party focus on select, Democrat-run cities in six states, but they also padded the Biden vote in all of the other states, even solidly Republican states like Indiana.

Why would they do this? Why would they bother with states like Indiana when they would have enough electoral college votes without it after stealing the six states above?

Presumably because people would have a hard time believing that Biden won Wisconsin and Michigan if he were to get completely wiped out in Indiana. It would be about impossible to believe he won Pennsylvania if he couldn’t come anywhere close to winning Ohio, a bellwether state. It would just be too obvious that something had been done in those select six states. And this would draw scrutiny.

But if numbers could be pumped up everywhere — if the Biden vote could be padded in all 50 states, at least in a dozen or so counties in each state — then everything might look at bit more believable.

What About Indiana?

So what do we know about Indiana and election integrity? How secure is your vote here?

It’s not secure at all.

Indiana is one of only eight states in the country that in 2020 was still using voting machines that have no paper ballot back-ups. Sixty percent of voters in the state live in counties using these kinds of machines (called DRE machines), according to a study that was released in October of 2020 by the Indiana University Public Policy Institute.

This makes Indiana the state with the fifth highest percentage of counties using machines with no paper backup — after Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey and Tennessee.

The problem with these machines is that you can’t audit the vote. There are no paper ballots that can be counted as a check against the numbers that show up on the voting machine printouts.

It’s as though you’re working in a busy retail store and at the end of the night, you don’t count the cash drawer. You just go from the computer print-out and have to trust that that is how much money was received that day. No one does this. You always, always, always count the drawer as a check against the machine. You don’t just take it on faith that the dollar amount that shows up on the computer printout is the amount of money in the cash drawer. That would be insane.

And this is just money. When we’re talking about votes, we’re talking about something much more precious: the health of the nation, and the confidence that we are really being governed by those who have our consent. It’s hard to understand how Indiana could have allowed these machines for so long. And it’s interesting to see where they’re being used.

Voting machines with no paper backups are being used in three of the four most populous counties in the state: Lake County (Hammond, Gary), Hamilton County (Carmel, Fishers, Noblesville) and Allen County (Fort Wayne).

This is interesting because Lake County, in the northwest corner of the state, was identified by former intel guy Seth Keshel as having the highest number of what appear to be “excess votes” — votes that are over and above what can be expected from looking at voter registration numbers and population trends.

Keshel was one of the presenters at Mike Lindell’s cyber symposium in August and is pushing for full forensic audits to be done in every single state. His contention is that there are a minimum of 8 million excess Biden votes across the nation.

Hamilton County is another one of the counties in Indiana he identified as having many more votes cast in November 2020 than one would expect — a suspiciously high number.

Hamilton County, of course, is the famously Republican county just north of Indianapolis, and the county with the highest average household income in the state. It’s also the fastest-growing county in the state for the fifth decade in a row, and grew 26.5 percent between 2010 and 2020.

The Hamilton County Numbers

The big election night news here was that the city of Carmel, the largest city in Hamilton County, went for Biden. It was the first time in its history that Carmel had voted for a Democrat for president.

“I don’t believe it,” a friend of mine who lives in Carmel said flatly in a recent phone conversation. She works in real estate. She knows every neighborhood in Carmel, and loads of people, including newer residents who’ve moved there in recent years.

Carmel frequently makes it onto those lists of “best city in America to raise a family” and other such lists given its top-notch public schools, low crime, great jobs and good urban planning (it has more round-a-bouts than any other city in the country). A lot of new people have been moving in — people from Chicago and the east coast — and many tend to be more moderate. But this doesn’t really explain things.

Look at the numbers.

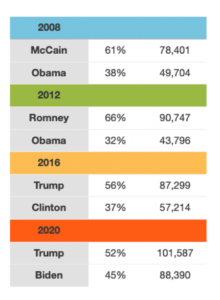

Trump won Hamilton County, as would be expected. In fact, he got a big increase in votes in the county, going from 87,299 votes in 2016 to 101,587 in 2020, an increase of 16 percent.

It’s funny, because it’s the same thing I saw when looking at the upper-middle class suburbs around Milwaukee: Trump increased his vote by 10 to 18 percent in almost every town and village in the Milwaukee suburbs. It was clear that some of these Republicans – educated, upper middle class — had been unsure about him in 2016, but now were happy with what he had done as president in four years.

But the Biden vote was something else altogether. Joe Biden got 88,390 votes in Hamilton County in 2020, which is 54 percent more votes than Hillary Clinton got in 2016, and 101 percent more than Barack Obama got in 2012. To put it another way, Biden got almost exactly twice as many votes as Obama did in 2012.

Yes, yes, Hamilton is the fastest-growing county in the state. But it’s not growing quite that fast. A rough workup of the numbers seems to show that the only way Biden could have truly gotten 88,390 votes in Hamilton County in November 2020 is if about every new person of voting age moving into the county between 2012 and 2000 was a Democrat —like, every one.

This is just barely possible. It’s also ridiculous.

Below are the election results for the last four presidential elections in Hamilton County.

Between 2010 and 2020, the population of Hamilton County increased by 26.5 percent, going from 274,555 people in 2010 to 347,467 in 2020. That’s an increase of about 73,000 people.

But . . . 26.2 percent of the population of the county is under 18 and can’t vote. When you take out the under 18s, you’re down to 54,750. But that was over 10 years. If you want to compare 2012 with 2020, you have to take out another 20 percent (assuming that the rate of population growth was more or less steady over that decade).

This gives you about 43,800 new residents of voting age between 2012 and 2020.

But Biden got 44,595 more votes in 2020 than Obama did in 2012, when we can assume that every Democrat who had a bit of breath in him would have come out to vote for the popular president.

If younger people make up a larger share of those who are moving into the county, people less likely to have children, it’s possible that 44,595 new residents of voting age moved into the county in those eight years. Entirely. But like I said, every single one of them was a Democrat? Every single one of them was an American citizen and therefor eligible to vote? Every single one of them registered to vote?

Ridiculous.

Hamilton County needs to be heavily scrutinized.

First, what do we know about it?

We know that in a September 2020 study, just two months before the 2020 general election, Judicial Watch identified Hamilton County as having the worst-maintained voter roll in the state. The number of names on the county’s voter registration roll exceeded the number of eligible voters in the county by 113 percent, they found. But that was with the census estimates.

With new census numbers having since been released, we see that Hamilton County’s voter roll still shows more people registered to vote in the county than the number of people age 18 and up who live there – thousands more.

As of Nov. 3, 2020, there were 260,082 registered voters in Hamilton County, but only about 256,430 people age 18 and older living in the county.

Not good.

Why would the voter roll in the county have so many people on it who have either passed away or moved away? Why isn’t this voter roll being maintained?

Section 8 of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, commonly known as the Motor Voter Law, requires that states and counties maintain voter rolls and have a system for regularly removing people who had passed away, moved away, or become ineligible for some other reason.

Indiana has been sued twice for failure to maintain its voter roll: the first time in 2006 by the U.S. Department of Justice and the second time in 2012 by Judicial Watch.

The Judicial Watch suit notes: “The State of Indiana has a history of failing to comply with its obligations under federal voter registration laws.”

On somewhat of a side note, the suit also notes that when the organization sent a letter to the state of Indiana – to then Secretary of State Charlie White and also the Indiana Elections Division co-chairs Bradley King, a Republican, and Trent Deckard, a Democrat – pointing out this problem with its voter roll and indicating its intent to file a lawsuit, King and Deckard bizarrely misunderstood, and wrote back denying what they said was a “grievance” and misspelled the organization’s name.

This is what King and Deckard wrote:

“IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED . . . That Co-Directors having determined that the complaint or grievance filed by Justice Watch, Inc. (sic) with the Election Division (and designated as 2012-1) does not set forth a violation of NVRA or IC3-7 even if the facts set forth in the complaint or grievance are assumed to be true, hereby DISMISS the complaint or grievance.” (Emphasis original)

At some point, King and Deckard realized that they were being sued, and that it wouldn’t be up to them to affirm or deny the so-called “grievance” — a judge would be doing that.

After considering this reality, perhaps with the help of their attorneys, they realized their mistake and agreed to clean up Indiana’s voter roll. I’ll come back around to King in a minute.

The suit was settled in 2014, with Indiana committed to taking several steps to remove ineligible voters from the rolls.

But here we are again, with voter rolls not being maintained.

The person in charge of elections and responsible for maintaining the voter roll in Hamilton County during both of these suits and after was Kathy Richardson, now known as Kathy Williams. She was the elections administrator in Hamilton County for more than two decades while also serving as a state representative. She’s now the county clerk.

Williams was the person who was in charge of elections in Hamilton County when the county began using voting machines with no paper trail that are manufactured by the Indiana-based company MicroVote General Corp.

The McKinney Tally

In the primary in 2020, something happened that could give us a clue about what may have happened in the 2020 general — or, to be more direct about it, about what someone might have done.

A longtime county councilman named Rick McKinney, a fiscal conservative who had almost always been the top vote-getter in Hamilton County, suddenly lost his primary to a woman who appeared to have only recently become a Republican.

“I tried not to, say, I have sour grapes or whatever,” he told me in a recent phone conversation. “But the first couple of days I was in disbelief or shock at how I could have lost coming from four years earlier being number one to then being number 5 of 7. My issues did not change.”

What was interesting was that just a couple of years earlier, he had opposed the proposed purchase by the county of MicroVote poll books and proprietary software, saying he was worried the electronic data could be used to benefit favored candidates, and not made equally available to all. It was a million-dollar contract, and by opposing it, he held it up for two years.

It was in the next election, in the primary in 2020, that he lost his race for re-election. He hadn’t even come in second or third. And shockingly, he’d lost Carmel.

“She beat me by 3,800 in Carmel and I had always dominated Carmel,” he said. “And this time I came in fourth or fifth in Carmel and I had always been number 1 or number 2, for 24 years.”

There was no major controversy, nothing that he can think of that would have caused voters to turn on him. “My core issues were the same: public safety, parks and infrastructure, which has never been a problem,” he said.

What also struck McKinney as odd was that on the ballot, his name was in between two challengers, who had both won.

He wondered how that was possible. He also wondered why, when the election results were reported, the names were not in ballot order, saying this had never happened. He’d called the county elections office, and they told him to call MicroVote.

“I got ahold of the MicroVote programmer and he quickly said, ‘Oh, they requested that order,’” referring to the county elections office. But the county elections office told him they hadn’t requested it.

I ask if he thinks it’s possible that MicroVote could have retaliated against him for holding up their contract for two years.

“Absolutely,” he says. “I try not to think about it, because it would probably make me cry at night.”

It wasn’t long after I talked to him that I found a news report of a similar incident involving MicroVote machines in Johnson City, Tennessee, just six years earlier, also in a primary. The county’s election website showed that the incumbent had won, but in fact, the order of candidates had been flipped, and so the wrong vote totals were assigned to the wrong candidates. It was called a gaffe, with MicroVote saying a programmer had forgotten to hit “save” on the controlling computer when he’d put the candidates in proper order.

In Hamilton County, there is now a new elections administrator. Her name is Beth Sheller. The 2020 election was the first presidential election in the county under her watch. When I talked with her by phone in late August, she assured me that the MicroVote machines aren’t connected to the Internet and can’t be accessed remotely and therefor are completely secure.

I asked her if she’d seen the New York Times article from 2018 entitled, “The Myth of the Hacker-Proof Voting Machines.” She had not.

I’ve mentioned this article to other county clerks and elections administrators and have yet to come across one who has read it, or even heard of its existence. It’s very strange.

The article is maybe one of the best pieces of journalism ever produced on the topic of election security – in particular, the security of voting machines. In the piece, a county elections office in Pennsylvania is surprised to find out that its voting system is connected to the Internet when they were 100 percent sure that it was not.

They had no idea that a contractor working from home had tapped into it for 90 minutes the night before a presidential election. Ya.

The gist of the piece is that no voting machine in use in America is hacker-proof. Even if the voting machines themselves – the machines that people vote on at polling places — are not connected to the Internet, the election management computer that tallies the votes on election night often is. And all computers, of course, can be preprogrammed.

So what might have happened in Hamilton County? Or, to be more precise: What might someone have done? There seem to be around 30,000 excess Biden votes. Where did they come from?

One possibility is that either a MicroVote employee or contractor added votes for Biden.

Another possibility is that an outside hacker added votes for Biden.

But votes have to be connected to actual voters – or, at least, to names on the voter roll. And here is why it’s awfully convenient to have dirty voter rolls – rolls clogged up with the names of people who are deceased or no longer live in the county. A bad actor – a MicroVote employee or contractor or an outside hacker – could “assign” the extra votes to names on the voter roll who had not yet voted.

It’s also possible that the extra votes were added by means of absentee ballots. Of Biden’s reported total of 88,390 votes in Hamilton County, 16,074 were from in-person voting on Election Day, 25,796 were from absentee ballots (mail voting) and 46,520 were from walk-in voting prior to Election Day (early voting).

What Is to Be Done?

Even though the voting machines have no paper trail, I believe that there are some things that can be done and should be done to try to find out what might have happened in Hamilton County.

One would be to determine what records exist, paper and electronic, that recorded vote totals at various times during the day on Election Day and election night on the election management computer, and then to submit a public records request to get those records.

Another would be to narrow the focus to a few precincts, and to plan a canvas of these precincts, on weekends when people are likely to be home. I’ve picked out five precincts in Carmel that Trump won in 2016 but somehow lost in 2020. They are Clay Northwest 2, Coxhall, Clay Center 1, Saddle Creek and Spring Farms. A voter roll can be requested from the county showing the names and addresses of all of the people in a particular precinct, and whether they voted in the 2020 general election (though of course it won’t show for whom they voted). The roll can be requested as a walk list, or can be ordered this way by someone with a bit of skill, so that canvassers can walk from house to house. The goal would be to find out if the voter listed on the roll does in fact reside at that address, and whether he or she did in fact vote in the 2020 presidential election. What might canvassers find? Maybe that someone who is shown as having cast a vote in Hamilton County hasn’t lived there for some time. Maybe that someone who is shown as casting a vote in Hamilton County cast a vote in another state or county, and their Hamilton County vote was stolen. Maybe that someone shown as having voted in Hamilton County is in a nursing home elsewhere and did not in fact vote, or is deceased. Maybe that there is no one by the name listed on the roll as having voted in the county actually living there.

The entire roll should also be scrutinized, and checked for double names, double votes and people voting in more than one county. More than 20,000 college students likely reside in Hamilton County, at least part of the year. How many of them voted in their college town and also cast a vote in Hamilton County? The entire roll should also be scrutinized, and checked for double names, double votes and people voting in more than one county. More than 20,000 college students likely reside in Hamilton County, at least part of the year. How many of them voted in their college town and also cast a vote in Hamilton County?

Concerned citizens should also immediately form an organization to press for a full release of all data related to the November 2020 election, and should insist upon an independent review of the MicroVote voting system by outside computer security experts.

MicroVote machines were used in Indiana in November 2020 in the following counties: Adams, Allen, Bartholomew, Blackford, Boone, Clay, Clinton, Daviess, Decatur, DeKalb, Delaware, Dubois, Fayette, Fountain, Franklin, Grant, Greene, Hamilton, Hendricks, Huntington, Jasper, Jay, Jefferson, Johnson, Knox, Kosciusko, LaGrange, Lake, Laporte, Lawrence, Marshall, Miami, Morgan, Noble, Orange, Owen, Parke, Perry, Pike, Pulaski, Putnam, Randolph, Rush, Scott, Shelby, Spencer, Starke, Steuben, Sullivan, Tippecanoe, Tipton, Vermillion, Wabash, Warrick, Wells, White and Whitley.

Note that in all of these cases, these MicroVote voting machines have no paper ballots. Thus there is nothing to audit — no way to do risk-limiting audits following an election to verify that the voting machine tallies are accurate.

But some other counties are being audited after every election. Under a pilot program begun by former Secretary of State Connie Lawson, some audits of the election results were done in some counties following the 2020 election.

The strange thing is, the Secretary of State’s office won’t tell me which ones.

I’ve emailed, and I’ve called. And they won’t tell me.

On Aug. 18, after getting stuck in traffic in Martinsville and arriving late to the Indiana Government Center and missing the entire Indiana Election Commission meeting, I was determined to get some answers. I went upstairs to the Indiana Election Division office and walked in the door.

I had called this office maybe 25 times between January and June. In most cases, no one picked up the phone. Several times, I’d left messages for the Republican co-director, Brad King.

In the last voicemail message I left, I urged and pleaded for him to return my call. I said I wanted to find out which counties were audited in 2020, and to get those audit reports. He never called back. I also left messages for Valerie Warycha, the Republican lawyer for the Election Division, asking her to call me with this information. I also emailed her. I never got a response.

I’d also contacted VSTOP, the organization at Ball State University that examines and certifies voting machines used in the state for the Secretary of State’s office. They emailed back, telling me to contact Valerie. But Valerie refused to respond. I’d also submitted a public records request for all election audits done in the counties in 2020, and hadn’t been able to get it.

So now I was doing what reporters do when public officials don’t return their calls: Show up at their office and refuse to leave until you can get some answers.

Valerie Warycha came out first. I asked her point blank why she hadn’t returned my calls and emails requesting the audit reports, and she responded that it was decided at the time not to provide me the information. Stunning.

Brad King came out next, and I asked him which counties were audited in 2020. He didn’t know. I asked him to find out. He said he could not do it. I would have to submit a public records request.

I submitted the request right then and there, scribbling it out on a page in my reporter’s notebook and handing it to him. His office responded by email a few weeks later, saying they don’t have the records, and to contact the Secretary of State’s office. I already have. I submitted my public records request for the audit reports to Secretary of State Holli Sullivan’s office almost four months ago. They are now in violation of the law, and willfully withholding these audit reports from me, and from all citizens of this state.

If we want answers, we have to press people. If we want audits, we have to insist upon them. If we want to prove the Indiana vote for Biden and maybe other candidates like Gov. Eric Holcomb was padded, we’re going to have to prove it ourselves. And the public officials who are standing in our way, blocking access to information and refusing to conduct audits, are going to have to be replaced.

(Click here to learn how Judicial Watch Forced Indiana and Ohio to clean up their voter rolls.)

Margaret Menge is an adjunct scholar of the Indiana Policy Review Foundation and a veteran journalist living in Bloomington. She has reported for the Miami Herald, Columbia Journalism Review, InsideSources, Breitbart, the New York Observer and the American Conservative. Menge also worked as an editor for the Miami Herald Company and UPI. A version of this essay was distributed by The Center Square/Indiana.